Vet Never Opened Medals Drawer After Army Addictions

Nina Burleigh

For Bloomberg

For a while when she was living on the streets, Nira Williams sold beer for $1 a can to the drunks who hung out at the shelters in Phoenix. She didn't imbibe herself. Alcohol, she said, is one thing she didn't get hooked on when she was in the U.S. Army.

The former private first class said she became an addict -- to prescription painkillers, to heroin, to most any drug she could score -- while stationed in Iraq, Germany and Texas. She wasn't tested in the combat zone, she said, "but I was dirty for sure." She was kicked out because of her heroin abuse in October 2010. Then she was homeless.

Until she found temporary work peddling soft drinks in a stadium, she said, she and her boyfriend got cash by bootlegging beer they pinched from convenience stores. They slept in parks or abandoned houses.

Sitting under a palm tree in downtown Phoenix as the temperature soared, her shorts drooped past her knees. She had trouble keeping her eyes open. She began to weep. A few miles away, at her foster mother's house, the medals she earned were tucked away in a drawer that was never opened.

"None of that stuff matters anymore," she said. "Most people I talk to won't even believe I was in the military."

Williams is 25, a casualty of a surge in substance abuse in the armed services that a Pentagon-commissioned report described as serious enough to constitute a "public health crisis." She went into the Army healthy, and she came out sick.

'Unacceptably High'

"The people that were in charge of her, they did her a disservice," said JoAnne Harner, 62, who with her late husband took Williams in when she was in the second grade. "Do I blame the military? Yes. Absolutely. She's not the person she was."

While not as rampant as during the Vietnam War, Williams said what soldiers referred to as self-medication is rife. The causes aren't confined to conflict and combat wounds. Williams didn't engage in firefights; she didn't lose a limb. Even soldiers who never left the U.S. were counted in what the Pentagon-funded report called "unacceptably high" abuse of drugs and alcohol.

Sent three times to rehab, Williams said she was rarely sober after each release. She tried to kill herself with one of the host of medications that were prescribed to help her.

The military's approach to treating addiction is outdated, and it's not surprising a former soldier could end up like Williams, said Thomas Kosten, a professor in the Psychiatry and Neuroscience departments at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston who's counseled addicted vets for 30 years.

Catch-22

There's little chance of success if an addict is sent from in-patient treatment back to the active-duty military, where proper "follow-up care seems to be almost nonexistent," said Kosten, a member of the U.S. Institute of Medicine committee that wrote the report, which was released Sept. 17.

What's as tragic, he said, is that Williams couldn't tap U.S. Veterans Affairs Department services at home because her heroin abuse resulted in an other-than-honorable discharge.

"This case is an example of some of the worst things that happen," said Charles P. O'Brien, chairman of the Institute of Medicine panel and head of the Center for Studies in Addiction at the University of Pennsylvania's Perelman School of Medicine.

It's a Catch-22. "They get into trouble in the military," O'Brien said, "and they can't get VA benefits later on."

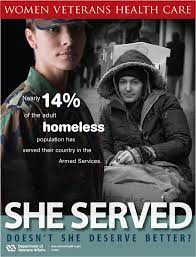

Substance abuse is a main cause of veteran homelessness, and VA Secretary Eric Shinseki said in a Sept. 13 speech that he has asked for a review of whether prescription drug policies "contribute somehow to the addictions we're dealing with."

Troubled Vets

The Pentagon is analyzing the Institute of Medicine report and its recommendations, said Cynthia O. Smith, a U.S. Department of Defense spokeswoman. "We want to do the right thing," she said in an e-mail. "The health and well-being of our service members is paramount."

Most who served during the country's longest period of sustained conflict aren't like Williams -- most don't have post-traumatic stress disorder, most don't abuse drugs, most don't end up on the streets.

Still, the military is discharging enough troubled ex-soldiers, and enough who can't get government help, to strain services, said Terry Araman, a Vietnam veteran and director of the Madison Street Veterans Association in Phoenix.

"The thing that keeps me up at night is that we have a million of these people coming home and society is not prepared for them," said Araman, who saw Williams when she used one of the nonprofit's computers to access her Facebook account.

A post from August: "i am addicted to my own lonliness."

Foster Kids

Williams is the eldest of three, born to a single mother and raised in Rathdrum, Idaho. When she was seven, Harner said, she ate Super Glue and called 911, replying when police asked where her mother was, "She's out looking for a man."

That's when Harner said child services officers sent Nira to her and her husband, Paul. A homemaker and a truck driver, they had elk in their back yard and a house full of foster kids. After rough patches, Harner said, Williams grew into a vivacious young woman with a warm heart and goofy sense of humor.

"We used to call her the baby-whisperer," she said. "She could pick one up and she had this funny way of holding them, and in seconds they were calm and asleep."

It was Paul Harner, ill with the cancer that would kill him, who suggested the Army when she dropped out of North Idaho College in Coeur d'Alene after a year; she'd spent most of it partying, not studying. She enlisted in June 2007 and 11 months later headed to Iraq with the 69th Transportation Company. She was a truck driver, just like her foster dad.

They could hear how excited and happy she was when she called home, Harner said. "She was always wanting to tell Paul, 'I learned how to back up and load this thing!'"

Few Women

In Iraq, she and her "battle buddies," as she called them, traveled in convoys, alert for snipers and improvised explosive devices. A mission, called a turn-and-burn, could last 36 hours. "You don't stop -- you just go and drop off and go again," said Sergeant Sean Clark, one of Williams' supervisors.

The work was grueling, and Williams said it was a slog for the women. She said females had escorts at distant bases, because there were so few of them and so many men. "I'd have to have three guys posted around me just to go to the bathroom," she said, and got leers at meals. "It was so bad I didn't want to go to chow hall."

In 16 months, she earned an Iraq Campaign Medal, an Army Achievement Medal, a Global War on Terrorism Service Medal and Army Service and Overseas Service ribbons, according to records obtained under a Freedom of Information Act request. The bosses could rely on her, Clark said. "She was a good soldier."

'Not Rare'

That was true, Williams said, at least until she injured her shoulder during a touch football game and was prescribed painkillers. The descent began. She said she was able to obtain 20 pills a day, snorting what was inside them to feel the effects faster, sometimes sharing with her buddies. She said she knew that "I had probably got myself into trouble."

It was just so easy to get refills on base that she had little incentive to stop, she said. "Her case is not rare," said the University of Pennsylvania's O'Brien. "Medics are fairly liberal" with painkillers in combat zones. And urinalysis screenings that might detect abuse aren't usually conducted in theater, said Major Stephen J. Platt, a spokesman for the Army at the Pentagon.

Williams said some officers knew. "They commented a couple times, hey, why you going to the doctor every other day?"

When her unit shipped out to Mannheim, Germany, she said the flow of easy meds was cut off. She got her combat pay, thousands of dollars, so much "it was like Monopoly money." And she and her buddies turned to pure heroin, buying it in Frankfurt and bringing it back to the barracks.

Guns Outside

"It was insane," she said. "I don't know why we didn't die." They were so bad at hiding it that the Army Criminal Investigation Command found out, and opened a criminal case.

William's next assignment was at Fort Hood in Texas. On her way there from Germany, she visited Harner, who said she was shocked to see her foster daughter doped up, slurring her words. "At night she would wake up screaming," Harner said. In the daytime, "she thought there were people outside with guns."

In Texas, Williams said, she combated anxiety and insomnia with pot and downers, and decided to volunteer for Afghanistan. While experience suggested otherwise, she told herself, "If I sign up, I will go off drugs."

It was Nov. 5, 2009, when she went to the Soldier Readiness Processing Center, the day Major Nidal Malik Hasan allegedly shot and killed 13 people. Williams said she was outside when soldiers in her queue ran, screaming, and she ran with them.

Polysubstance Abuse

She gave up on Afghanistan; she said she took so many downers she scared herself. Three days before Christmas, she checked into the military unit at San Antonio's Laurel Ridge Treatment Center. "I self-reported to my command about my drug use and they sent me here," she said on the admitting form.

At Laurel Ridge, Williams was diagnosed with PTSD and polysubstance dependence, according to her medical records, released under the FOIA request.

Her first term in rehab lasted 35 days, and it didn't take. About two weeks after her release, she went AWOL. She called Harner from Dallas, saying she didn't know where she was, and a family friend collected her and drove her back to the base. First Sergeant Charles Anderson, who's since retired, said she was so messed up he escorted her to Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center. She was sent to Laurel Ridge again.

There for more than two weeks this time, she "participated 100 percent" in programs for PTSD and cocaine, cannabis and opiates abuse, according to a doctor's note on her release papers. Back at Ford Hood, Williams said, she started using almost immediately.

Heroin Investigation

Debra Ward, a spokeswoman for Laurel Ridge, said she couldn't comment on any patient's case because of medical privacy laws. Platt, the Army spokesman, said officials couldn't discuss the former soldier's medical treatment, also citing privacy laws.

The CID heroin investigation was still under way, and on March 15, 2010, Williams signed a statement: She admitted using the controlled substance "many times" in Germany and buying some for a soldier.

"I'm the kind of person who can't tell a lie," she said, lighting a cigarette butt in Phoenix, still shaken hours after she was kicked out of a market where she'd tried to steal lunch.

Working in the motor pool after she signed the confession, Williams continued to smoke pot and take painkillers. In Idaho, Joanne Harner worried when the phone rang.

Xanax Overdose

"Every time she called, you just wanted to throw up because you can't do anything," she said, wiping away tears. The call on May 18 was the worst. "She was hysterical." Williams had been raped, she told her foster mother. Williams reported it the next day, and the CID opened an investigation.

On May 26, investigators got approval to outfit Williams with a wire while she met with the man she accused, a soldier who outranked her, "to confront him about the sexual assault," according to CID documents.

Instead, according to the documents, the exchange focused on whether she was too drugged up to remember what had happened. She'd taken a sleeping pill the evening of the alleged rape.

Her failure to elicit anything incriminating was devastating, she said. So was what she said the man told her: Nobody would believe her because she was an addict. "That just mentally killed me."

In June, she took an overdose of Xanax, an anti-anxiety drug. "I felt like I was done with everything," she said in a monotone. "I had already lived a long and healthy life."

Case Closed

Her records show that besides Xanax, the medications she was prescribed while in Texas included the sedative Ativan, the antipsychotic Haldol, the antidepressants trazodone and Celexa, the sleeping pill Ambien and the sleep-disorder drug Provigil.

Using multiple drugs to treat a variety of conditions was identified as a "contributing factor" in suicides in a Jan. 19, 2012, Army report.

The attempt sent Williams to Laurel Ridge again. She was released July 13. Two weeks later she was charged with possessing, using and distributing heroin in Germany.

Given the choice of a court martial or a discharge for other than honorable conditions, she chose the latter, signing a statement agreeing to the separation on Aug. 3. The rape investigation ended later that month, when the CID concluded there was insufficient evidence the man she accused had "forcibly performed a sexual act." The case was closed.

Cutting Losses

In her last months in uniform, Williams was hospitalized several times at Darnall, diagnosed with adjustment disorder and bipolar disorder, according to the records. An attendant wrote in an undated note on her chart that she cried, saying, "The girl inside of me is going to kill me." She hit the wall, the attendant wrote. "'She hurts me,' digging at arms. Who? 'The girl in the mirror.'"

On Sept. 21, she left Darnall with instructions for her commanders. Williams should be in "LINE OF SIGHT SUPERVISION" at all times and have "NO ACCESS" to items including knives, razors and bleach, a nurse wrote, using capital letters.

Anderson, her first sergeant, said Williams slept on a cot near his office so he could keep an eye on her. When her discharge came through in October, the Army gave her a bus ticket, to Idaho. Harner by then had moved to Phoenix.

Williams' treatment probably fell short, Anderson said. "She should have been there longer," he said of her hospitalizations. "Let's get the problem fixed." At the same time, he said the Army could only do so much. "I'm a compassionate person, but we are trained to deploy," he said. "You gotta cut your losses. Nira went to the end of her rope."

'They're Here'

Harner arranged for Williams to get to Phoenix, and took her in. "I would wake up in the middle of the night," Harner said, "and I'd find her hiding in the corner under the stairs, saying over and over, 'They're here, they're here.'"

Was she recalling Iraq, or was she delusional from drugs? Williams said she doesn't know. Harner didn't have resources to pay for rehab. Williams kept using, and stole $40,000 of jewelry and electronics from Harner in July 2011. While she didn't press charges, her foster mother told her she couldn't live at home until she got clean.

She never went back. Her possessions fit into a knapsack. Sometimes she stank of the hallucinogenic herbal mix called spice that her street companions smoked. She lost 30 pounds, and spent time in a city detox center, trying to get clean.

A veterans advocate put her in touch with a VA official who could help her file a special request for benefits. After contacting the VA about it, she didn't follow up for months, disappearing into the streets. Then, two months ago, two years after the Army kicked her out, the VA ruled she was eligible.

VA Housing

The agency has "some discretion" over a veteran's eligibility after reviewing "facts and circumstances," though it can't alter the type of his or her discharge, according to Monica Cabrera, a spokeswoman for the VA in Phoenix, who said she couldn't comment on Williams's case.

For the past three weeks, Williams has been living at a substance abuse treatment halfway house in Phoenix. She's a member of Narcotics Anonymous, is under the care of a VA doctor and attends therapy sessions with other female veterans, she said in a telephone interview last week. She's about to move into VA housing, a one-bedroom apartment with a big closet that she toured after Thanksgiving.

"I was worthless the last two years," she said. Now she's clean, and looking for work. "All she needed," her foster mother said, "was some help."

(Adds comment from Pentagon official in 16th paragraph.)

December 7, 2012, 5:08 PM EST

Leave a comment